Article: Paris: The Character of Changing Light

In the fall of 1990, I was asked to write an article about my experiences of photographing Paris. I began thinking about what I had accomplished after six years of looking at the city. I then thought back to the last day I was there when something totally unexpected happened which affirmed to me something quite telling about my work and about my thoughts of seeing Paris change. Of all my experiences in the city, it was several hours at the end of that spring day in 1989 that stays with me most. It is how I remember Paris.

In the fall of 1990, I was asked to write an article about my experiences of photographing Paris. I began thinking about what I had accomplished after six years of looking at the city. I then thought back to the last day I was there when something totally unexpected happened which affirmed to me something quite telling about my work and about my thoughts of seeing Paris change. Of all my experiences in the city, it was several hours at the end of that spring day in 1989 that stays with me most. It is how I remember Paris.

April 27, 1989 was the last day I was in Paris, nearly six years after I first came to the city. As usual, April was wet. It wasn't cold, but the day was grey and threatened rain. I left my small hotel on the Rue de la Grande Chaumière in Montparnasse early in the morning and walked up to the corner and around to the Café La Rotonde on the Boulevard du Montparnasse.

Soon after I first came to Paris, La Rotonde became home. From my seat along the edge of the sidewalk, I began each day watching the city wake: early morning deliveries of produce to restaurants, the blossoming of tables and chairs onto the sidewalk, students walking in groups arm in arm to the local schools, residents stopping into the cafés for coffee, to read the paper or argue politics and the opposite sex before going to work.

Around the corner from La Rotonde is the Rue Vavin, a short, neighborhood street lined with retail shops, night clubs, small hotels and brasseries. It connects the Boulevard du Montparnasse with the Jardin du Luxembourg, the grounds of a seventeenth-century palace that has been transformed into a splendid park. Of all the magnificent places in Paris, it is my favorite spot of all.

I headed east along the south side of the gardens and its tall cast-iron gates, past the tree-lined edges of the Place de L'Observatoire and the long view of the palais, and turned north onto the Boulevard Saint Michel toward the center of the town.

It began to drizzle as I crossed the Rue Soufflot and the lamppost-paced vista east of the Panthéon. The towers of the Conciergerie and Notre Dame became visible as I descended Saint-Michel toward Saint Germain--a wide, bustling street that gently arcs from one point of the Seine to another, defining the southern edge of the Latin Quarter and the older portion of the Sixth arrondisement. This is the heart of Paris where the streets are small and short and cross at various odd angles creating a labyrinth in which one can comfortably lose one's way. And the names of the roads have nearly as much character: Rue des Saint André des Arts, Rue du Chat Qui Pêche, Rue des Grands Augustins.

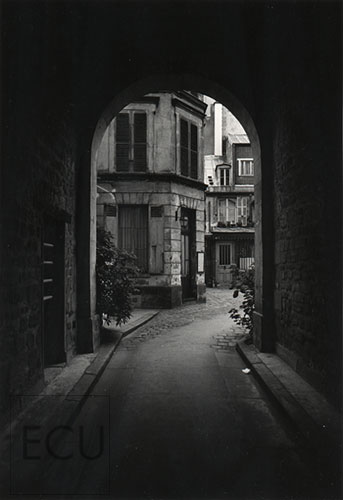

Here, one discovers the popular image of Paris, where you feel as if you've wandered into another time. Veinlike cracks run through chipped masonry walls that expose the unevenly baked bricks from past centuries. Streets and alleys are mosaics of cobblestones, washed shiny along the curbs by the constant flow of water. Pedestrian passageways connect a network of courtyards and old winding wooden staircases. Signs have accumulated, documenting type styles and regulations of different times, and the same iron lampposts, cast over a century ago, continue to illuminate the night.

But the historic core of Paris was not my destination today. I needed to spend most of the day several miles to the northeast. But on one's last day in the city, Paris has a way of drawing you to certain spots because you simply have to see them one last time.

In a little while, I would head to Belleville and Ménilmontant--older, once separate villages that were rapidly changing. I still wasn't satisfied with the pictures I had taken during this and previous trips of this area which has become a metaphor of what is happening to much of Paris. Here, the increasing destruction of the buildings and spaces that make up the traditional image of the city is occurring. Subsequent development of boxlike structures at best abstract the basic proportions of what was once there but which lack an understanding of the spirit that used to make architecture and the streetscape French. This vernacular spirit is found in simple features that are as useful as they are aesthetic: signage, shutters, shops along the street, the overall irregularity of development that brings unexpected discoveries in the alleys and courtyards that define paths and link a neighborhood, where chance encounters are always expected and the intimacy of common space forges a warmth of community.

I crossed the Seine, walking over the Pont Neuf to the west end of Ile de la Cité. At the open western edge of the island is the Place Dauphine whose enclosed triangular form echoes the shape of Cité. Inside the Place, the trees have grown tall and obscure and darken much of the space, making it difficult to capture the feel of the space on film. As with a number of other special corners of Paris--Contrescarpe, des Vosges, Furstemberg, and the Cour de Rouen--I was never able to photograph Dauhpine very well, even after many roles of Tri-X and visits during different times of the day and night, while it was clear and when fog moved low across the Seine softening the edges and details of the Place.

I descended to the Quai des Orfèvres on the south side of Cité and walked east along the river. The Seine itself is not a pretty body of water, often dark green or black, somtimes littered and noxious during the warmer months. But few walks are more splendid than along its quais, particularly around the islands of Cité and Saint Louis. And this is so at any time of day or season. The continuous masonry walls lining the opposing banks stand like stage sets, a harmonious ensemble of variously styled facades that were seemingly designed for the sole purpose of making visitors feel that they are in Paris.

The succession of small bridges crossing the Seine act as landmarks, indicating where one is in relation to the rest of the city, and they constantly vary one's focus while walking along the quais. Each bridge is distinct in design, and their series of arches stretching across the river frame views that change with nearly every pace. The city virtually disappears underneath each bridge as one's focus is drawn by a passing barge, rolled up mattresses, or a span's articulated stonework. And then just as quickly the city dramatically reemerges.

After passing a group of municipal buildings, the island's dense development suddenly opened up revealing the Place du Parvis and the tall Gothic outline of Notre Dame, which stood silhouetted under the day's dark sky. One block away, set on a small square behind the Hotel Dieu was the subway.

The station on the island is one of the deepest in city because of the depth in which the trains run beneath the Seine. The central north-south line that passes through here links with the system's concentric routes making it possible to reach nearly any part of the city with no more than a single transfer.

The Paris Métro is a remarkable creation. For me, setting off underground every morning to a different quarter of the city always involved an anticipation more akin to long-distance train travel than commuting. Stations are keenly decked with ornate kiosks, a few still don Hector Guimard's Art Nouveau styling. The ability to pass through turnstyles without delay with a Carte Orange begins to speak of the system's efficiency. Trains run every several minutes. Platforms are warmly lit, brightened by clean white tile walls and the constantly changing assortment of large, colorful advertisements. There is little graffiti, bums are generally respectful, and even the ubiquitous odor created by the friction of the trains' rubber wheels against the steel rails benignly brings back memories of previous trips around the city. Subway doors are opened individually by passengers flipping a handle, providing the rider with an unexpected sense of control. Inside, passengers are often treated to a variety of entertainment, courtesy of underemployed, often talented musicians, mimers, and puppetiers.

I transfered at the Gare de l'Est for the métro to Place Stalingrad in the 19th arrondisement where the city's canal system reemerges on grade. Above, a portion of another subway line runs elevated to the foot of Montmartre several kilometers away.

It was now raining harder. The streets cutting across the Place were wet and shiny. Buildings looked damp with their various shades of browns and grays deadened by the darkening sky.

I passed under the elevated tracks and came to the Rotonde de la Villette, an eighteenth-century collage of circular, triangular and rectangular classical architectural elements that originally served as a toll house. It is set on the edge of a newly created plaza, part of the overall revitalization scheme for this portion of Paris. New development along the canal is linking the plaza with the new Parc de la Villette. Today, however, the plaza's wide concrete spaces lined with saplings looked empty and cold.

I didn't know the area east of the canal very well. However, its overall configuration illustrated in the Plan de Paris--an indespensible street index and map--described a promising district. There were a variety of street types, the Bassin de la Villette, a large park, and most important, proximity to Belleville and Ménilmontant. However, like many of the districts around the perimeter of Paris, this area appeared common and poor. Cafés, small shops, lower income residences were plain, similar in character to the adjacent suburban villages. Walking throughout the city revealed a surprising proportion of comparatively ordinary districts that one does not expect to find in Paris.

I wandered for several hours through a heavy mist along streets that ran straight and were not very well defined. Vistas dissipated without event, storefronts were uninteresting, and there was little landscape. Some new development was interspersed throughout the area. But the modern metal, glass, and concrete surfaces seemed characterless, strangely consistent with the area's focusless design.

It began to thunder. The sound reverberated down the narrow streets. The view south from some of of the higher elevations of this quarter was partially open, and in the distance I saw lightening cutting streaks over central Paris. It then began to pour. Even with an umbrella, I was getting very wet, and though it was humid, the dampness was soaking into me and I suddenly felt very cold.

I turned into an anonymous looking café on the Rue du Rhin. Two men were standing at the bar. One looked at me as I walked in and then turned back to the other. Red and white checkered cloth draped unevenly over the plain square tables. The worn linoleum floor was wet and dirty from lunch-time visitors who sat quietly eating. Cigarette smoke hung stale in the air, and the windows were clouding from the heat inside the café. It was nearly two o'clock. I had taken a half a dozen shots all day, nothing good, and if the weather remained the same, there was perhaps four or five hours left to shoot.

I walked down the street to the Place Armond-Carrel where the 19th arrondisement's municipal hall is located. On the other side of the Place is the northern entrance to the Parc des Buttes-Chaumont. Previously the site of a quarry and dump, the park is one of the city's wonderfully preposterous creations of lakes, streams, waterfalls, grottos, and mountainous landscape--all manmade. The rain had just about stopped as I entered the park. Not far inside, the city completely disappeared and there were few landmarks to guide the unfamiliar visitor. I wound my way around the higher elevations, cutting across greens and stone paths, and slowly descended toward the southern edge of the park bordering Belleville.

Through the eighteenth century, Belleville was a small, quiet village. Its superb views of the city [its elevation actually higher than Montmartre's] attracted the construction of country residences of aristocrats and wealthy bourgeois. Then came a variety of cabarets, dance halls, and inns, patronized by Parisians of all social ranks.

By the mid-nineteenth century, Belleville had also become home to artisans and working class families displaced by the rebuilding of central Paris. Real estate speculators responded to this influx by building tenements. By the twentieth century, Belleville became a port for successive waves of immigrants from Poland, Armenia, Turkey, Yugoslavia, Algeria, Tunisia, and the French West Indies. Today, the area is Paris' foremost melting pot, colored further by the creation of ethnic cafés and shops that serve their respective populations.

Much of the irregular configuration of streets, small residences and shops, tenements and courtyards that wound down Belleville's steep grade is as poor as any part of Paris. While spared wholesale demolition during the city's mid-twentieth century fascination with chemotherapeutic renewal policies, the government has targeted Belleville for extensive rebuilding as part of an overall attempt to revitalize the eastern half of the city. Enlightened design guidelines are preserving the contours and grade of many streets, and new building is required to retain the neighborhood's basic scale. However, where redevelopment has occurred, Belleville was no longer to be found.

I walked south down the Rue de la Villette, passed rows of old and new apartment buildings. Some had been renovated, but their original character had been stripped away, making them appear neither new nor old. Several blocks further down I reached the edge of the 20th arrondisement defined by the the Rue de Belleville. This is a long, crooked street that slopes down toward the center of town. The low-rise buildings on either side step down along the street creating jagged lines of storefronts and cornices which frame a view of the Eiffel Tower that stood far off in the distance.

The neighborhood below the Rue de Belleville looked very different from the streets around Stalingrad. Most of the streets were short and narrow and almost none ran straight for more than a block. The characteristic labyrinth of Parisian streets reemerged, lined with traditional stucco facades with extensive courtyards behind. Some were maintained; others were littered with trash and broken bricks from small interior structures which had been torn down.

The streets were still wet, but they were no longer shinny. They took on a dull finish that began reflecting the light of the whitening sky. The increased brightness warmed the mood of the area, adding contrast and depth to the facades which had looked flat and ordinary during most of the day.

But soon after rediscovering this older piece of Paris, signs of change began to appear all around. One crain after another popped into view. Turning corners began to reveal cleared lots and fragmented edges of partially broken rows of mansard tenements. Colorful grids defined exposed side walls which read as fossils of the apartments that once stood next door. Sheer, contemporary, detailless concrete walls with punched windows appeared with increasing frequency. Some of these facades defined entire new blocks, strangely without a single shop or café.

Geometric fragments formed a new postmodern elementary school and apartment complex, whose moderate, pedestrian scale represented a vast improvement over recent residential planning, but which appeared more institutional than communal. Rather than linking with the street and adjacent properties, the public spaces around many of these projects were firmly defined by concrete parapets topped with iron railings. Lampposts, neighborhood map stands, and street signs were awkwardly ornate. Overtime, these metal and concrete surfaces will age hard without patina. Already reinforcing steel rods have begun to rust through masonry walls, and metal-paneled facades have lost their lustre.

In replacing a good deal of substandard dwellings, this new order of building has created no order at all. While this renewal effort involves far more benign architecture then the blocks and towers of the Grands Ensembles of the 1950s and 1960s, the result is nearly as anonymous. In a way, the strategy is even more destructive. Instead of limited to a specific site, an extensive network of infill and block-size redevelopment is being woven throughout much of the community. And with almost bland mitotic drive, each improvement seems to have increased the likelihood of redevelopment of adjacent properties.

As I walked further on, suddenly out of nowhere bounded the slopes of the new Parc de Belleville and the wide open views of the city to the south which had been largely obscured by over a century of development.

I traversed the winding paths of the Parc to the large water course at the bottom of the hill where many children were playing. It was late in the afternoon, and I was tired. The subway home was just a block south on the Boulevard de Belleville. But I didn't feel I should leave quite yet.

An enclave of small streets still remained at the edge of the park. It is difficult to tell if deterioration had been furthered by speculation or was simply the natural state. The door at 45, rue Toutille was cracked. I peered in and saw a small simple courtyard. The broken pavement was clean. Old tables, stools and apartment radiators were used as plant stands. Small, rectangular additions to the ground floor apartments expanded into the courtyard. An old woman was cleaning her kitchen that opened onto the space. She noticed me as she walked out into the yard. She turned back into the kitchen, then after a moment reappeared, a suspecting expression relieved by curiosity about why anybody would photograph her home.

"Qu'est ce que vous faites?"

"Prends des photos."

"Mais, pourquoi ici?"

"Parce que votre maison est d'un autre temps dans

lequel j'aurais aimer vivre."

"Vous voulez habiter comme ga? Vous êtes curieux

vous!"

She then smiled and turned back inside.

I walked east on the Rue Ramponeau and then passed a familiar site. Three years earlier I had extensively photographed 21, rue Ramponeau. I became intimately familiar with the details of the scene after several hours in the darkroom printing the image. When revisiting previously photographed sites, I become aware of the distortion of the most realistic looking photograph. Even with a normal lens, the perspective is off, the space is compressed, and an image which looks so true on paper reveals the camera's limitations when you return to the site.

The scene was of a boy standing inside a doorway off a small side yard. Above the door Concierge was painted in familiar nineteenth-century French serif type on the cracked stucco wall. Clothing was drying in the foreground and a large wash bucket was on top of a table. The side yard on the right narrowed with the staggered projection of two separate additions. This path cut through the ground-level of the furthest addition providing access into a central courtyard deep inside the block.

Now the alley was no longer defined. The adjacent building on the right had been torn down expanding the side space into a temporary street that slashed deep into the block. Much of the side wall of 21, rue Ramponeau was supported by a makeshift wooden buttress. All the windows were crossed with two by fours. I couldn't tell if the building was stabilized for subsequent renovation or being prepped for demolition.

I continued east up the Rue Ramponeau, passed the Rue Julien Lacroix which led back to the Parc de Belleville. Ramponeau's broken pavement was replaced with neat rows of cobblestones. On the right, a row of one- and two-story buildings were boarded up. A sign "Hotel" projected from the last building of the row before the street curved north.

I turned the corner and walked down the street toward the Rue de Belleville then turned around. At the end of the street, where the road bent, was the empty shell of the hotel, a four-story building with a small café on the ground floor. The two second-story windows had been hastily bricked up. An open single window with a balcony defined the third floor. Between the two fourth-story windows was a sign, HÔTEL DE LA BELLE VUE. I smiled as these images triggered a stream of memories.

I first came across the Rue Jouye-Rouve in 1986. Like this day, the weather was overcast and gray and similar in mood of the photographs taken by Willy Ronis whose book on Belleville and Ménilmontant encouraged my visit to this area. This was a part of Paris I had not heard of and was very much of the old city for which I was searching.

Redevelopment of Belleville was well underway by 1986. But this quiet, odd-shaped street was a living reminder of the neighborhood's more traditional character. Small, modest workshops and homes, a café, common courtyards, a six-room hotel providing temporary housing for new residents or for those displaced by demolition. It was not so much its appearance as it was a sentient mood of another time that made Jouye-Rouve so appealing. I knew what I wanted to express in a picture of this street, but looking at the proof sheets a month later back in New York, I realized I had not succeeded.

The following year, I again stumbled onto the street. Several adjacent blocks had disappeared. Three or four buildings on Jouye-Rouve had been abandoned. The street's character, however, was still alive. As with the Place Dauphine and the Cour de Rouen, I again was baffled in discovering a place that intrigued and yet proved so photographically intangible.

I looked at the scene from various perspectives, from different sides of the space, from atop steps and garbage cans, with lenses of different focal lengths. Still unsatisfied, I then looked at some of the details of the space. But when they too read quite plain, I decided to simply walk the street without thinking about what I wanted, hoping, like in writing when ideas untangle themselves when not thought of quite so intensely, the image would come to me. But it never did.

Now, today, a ten-foot cinder block wall enclosed an overgrown garden next to the hotel. From the sounds coming from behind the wall, it seemed that the garden had become a sanctuary of sorts for the neighborhood's animals. A black cat stuck his head through an opening in the wall. He looked around then quietly stepped out onto the street and bounded onto the hood of a small Renault. A larger white cat then emerged from the garden and sat just outside the wall. I dropped my camera bag and sat on the bumper of a car next to them. A man smoking a cigarette turned the corner of the street and passed by. The café on the ground floor of the Hôtel de la Belle Vue was boarded up with cinder blocks. Above, the windows were stripped of their frames. Light leaked into the top floor through the broken roof. A group of old tenements behind the hotel were in similar shape.

I imagined the housing was poor along much of Jouye-Rouve, and that there was much poverty, defining a place from which most residents were desperate to escape. And yet as a visitor I prefered resting on this small corner of this worn out block in Paris than in the pretty landscaped spaces of the Parc de Belleville just steps away.

I was surrounded by pieces of Paris I would never see again. I knew when I returned next to the city this space would be gone: the four-chair café, the hidden garden, the remaining shops that staggered down the street to the Rue Romponeau, the black cat. And I am also too aware that these words, like the pictures I have taken of the block, fail to convey the feeling of this street. Perhaps, all this is trite romanticism about a place that has simply passed its time. Even now, thinking back to the moment I spent sitting on this block writing these thoughts, I can't regain the peculiar sadness I felt. But I do remember feeling it, along with the distinct sense that I didn't need to take any more photographs.

*

It was 6:30. The clouds had lifted and patches of sunlight began filtering through to the street.

I didn't get the images I was looking for. It came to me that I never really could. I had brought much to what I had seen. At best, I can show space and details that begin to shape the mood of a place, and I can contrast the old and the new. But unless you've been here, there will always be a barrier between what I see and what I want you to feel.

I can tell a story of what is happening to Paris today. But I'll never express to you what I deeply sense because so much of it is a matter of the loss of rememberances past that have formed inside of me over many years, imparted through the images of Marville, Atget, and Ronis, Hemingway's simple descriptions, and my own experience of having seen so much of Paris change.

Eric Uhlfelder

New York City

24 October 1990